|

Storm on Cumberland Mountain.The Story of the Cowan Pusher DistrictBy THOMAS E. BAILEY

(This article is reprinted from Tennessee Historical Quarterly, Vol. XXIV, No. 3, Fall 1975. Pages 227-248. Copyright, Tennessee Historical Society, 1975.)

When they asked Dr. James Overton, one of the chief promoters of the Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad, how he intended to get a railroad over Cumberland Mountain, he replied, "Why, bore a hole through it, of course!'" This offhand answer made light of the difficulties involved, but it was typical of the outlook of the men who determined to build 150 miles of railroad through some of the most rugged country in the southeastern United States in 1845. When the directors of tae Nashville and Chattanooga set out to connect the cities of the corporate title with a strand of iron, they affirmed Dr. Overton's prophecy by tackling the most difficult part of the construction first. Before a single rail was laid anywhere on the line, construction forces were at work on the tunnel through the mountain.

The N&C had engaged John Edgar Thompson, a well-known civil engineer of the day, to make a preliminary survey of the entire route of the railroad. The results of the survey were remarkably accurate, and the railroad was built along the exact route described in Thompson's 1847 report. He also estimated the cost of construction at $3,130,000 for the entire project. The exact cost turned out to be· $3,255,189 according to the company's books. In view of the expertise exhibited by Mr. Thompson, it seems incredible that he made no charge whatsoever for his services. The directors of the N&C were so pleased with his work, however, that six years later they rewarded him with 3,000 shares of capital stock in the company. Thompson attained further fame when he later became president of the Pennsylvania Railroad.

Construction crews, including a large number of slave laborers, arrived at the tunnel site 87 miles south and east of Nashville in early 1849: The only tools available to them were the hand drill, sledge, pick, shovel, block and tackle, and wheelbarrow. The major ingredients involved in the work were muscle power and an uncommon amount of ingenuity. Torches provided the only light. Black powder, with its attendant suffocating smoke, was the explosive.

Chief Engineer James H. Grant began the work by sinking three vertical shafts from the top of the mountain down to track level. Each shaft was 7 feet by 11 feet in cross section and the average depth was 170 feet. With the shafts down to tunnel floor level, Grant was able to start crews excavating the solid rock in both directions from the bottom of each shaft. The work proceeded from the interior headings and from both main portals, affording a total of eight contact points. Three shifts worked around the clock during most of the construction period.

The bore was to be 2,228 feet long with a cross section 17 feet high and 12 feet wide. The grade from each portal ran upward to the center of the tunnel at an elevation of 1,147.3 feet above sea level. The three vertical construction shafts were left open and served as excellent ventilation ducts for the removal of locomotive exhaust gases.

By February of 1851 the tunnel was holed through. The citizens of Winchester and Cowan celebrated the event with a formal' ball on the 22nd, and afterwards many of the more hardy celebrants climbed to the tunnel and walked the length of the bore by torchlight. The night was bitterly cold, but the weather apparently did not deter those who had watched the construction for over two years and now saw the completion of a project they had never really thought would be accomplished.'

Trains began to use the tunnel early in 1853. Through the years the blast of locomotive exhausts wore a path in the ceiling of the tunnel along the centerline. As a precaution, the N&C built a special "tunnel car," a discarded box car with a special 6-inch braced timber deck applied over the standard roof. The car was run through the tunnel at set intervals while the crew stood on the deck and sounded the tunnel ceiling for loose rock. All loose material was removed by chipping, dropped on the special deck of the car, and hauled out of the tunnel.

The grade north of the tunnel averaged nearly 2 percent over the 2-mile distance from Cowan. To the south the grade ran to a 2.5 percent maximum and was 4~ miles in length. The south approach between Tantallon and the tunnel portal was the more difficult of the two, with 5 and 6-degree curves and with cuts up to 65 feet deep. On this grade the motive power of the N&C was tested to its ultimate.

A long siding had been installed at Tantallon to allow trains to pass or meet at that point on the single track main line. At the south end of the siding, in addition to the usual switch leading back to the main line, was another switch leading to a short spur known as the "runaway track." Northbound trains were required to wait for opposing trains on the main line at Tantallon with the switches set for the siding and runaway track. Thus, if a train moving down the mountain lost control, it would automatically be diverted into the siding and, if the momentum were sufficient, into the runaway track and the cornfield beyond.

The frequent unscheduled arrival of cars and locomotives in the cornfield eventually caused the railroad to revise its methods of dealing with the train control problem. Just after the turn of the century the siding and runaway track were relocated to the top of the grade at Rockledge, immediately outside the south portal of the tunnel. As before, the siding and runaway track switches were normally lined up with the main line. The new arrangement permitted trains to stop for a brake test prior to making the steep southbound descent. In later years a time delay device was added to control the south switch and runaway track. Thus, southbound trains were required to spend at least two minutes on the siding prior to proceeding. If they failed in this requirement, the runaway track, laid up grade for just such a contingency, received a visitor.

Control of the N&C Railroad passed from side to side with the advance and retreat of the armies during the Civil War. The railroad was, of course, a prime target for the cavalry operating behind the lines on both sides. By the late summer of 1863 the Federal armies had advanced down the line of the railroad to Chattanooga. Then, on October 9, a Confederate force under Joe Wheeler raided the Cumberland Mountain tunnel, driving the Union guards from the scene in search of reinforcements. Following that bit of reconnaissance, the raiders returned later in the month to blow up a Federal supply train at the north entrance of the tunnel. The tunnel was not damaged in this assault and, although an obviously vulnerable installation, survived the entire war without harm.

In the 1840's large deposits of coal were discovered on Cumberland Mountain near where Sewanee is now located. In order to ship this valuable commodity, the Sewanee Mining Company began construction of a railroad connection to the N&C main line in 1853. From the junction, just northwest of the tunnel, the line ran upgrade, crossed over the N&C main line at the tunnel portal, and continued up the west side of the mountain to Tracy City. The little mining road eventually came under the control of the Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company, which in turn was acquired in 1887 by the N&C's successor, the Nashville, Chattanooga, and St. Louis Railroad. An extension was built to Coalmont in 1904, and another to Palmer was completed in 1917.

The Tracy City Branch served both the University of the South at Sewanee and the large summer resort at Monteagle. The line had grades of nearly 3 percent and curves of more than 17 degrees. Little wonder the regular riders on the branch labeled their train the "mountain goat."

Grade reductions were being considered for a number of locations all along the main line of the NC&StL just prior to World War I in an effort to improve the efficiency of the entire operation. Serious consideration was given to electrifying the entire Chattanooga Division, including Cumberland Mountain, in lieu of reducing the grades over the difficult mountain terrain. Power for the project was to have been obtained from Hales Bar Dam on the Tennessee River. Projected revenues could not support the cost of the proposed electrification, however, and the idea was shelved in favor of some rather piecemeal grade reduction efforts.

Although the Louisville and Nashville Railroad had held a controlling interest in the NC&StL since 1880, the roads were not officially merged until 1957. Shortly after that the L&N decided to enlarge the Cumberland Mountain tunnel to a 21-foot ceiling clearance and a IS-foot width. The work, completed in 1960, allowed piggy-back shipments to be routed over the mountain.

The tunnel stands today as a monument to the men who built it, continuing to serve the purpose for which it was constructed over 120 years ago. A hogger leads a frightening life

It was apparent at an early stage that the locomotives designed for road service on the N&C were going to have difficulty in handling heavy trains over Cumberland Mountain. One solution involved breaking the train into parts and moving it over in two or more sections. This process, known as "doubling" or "reducing," was inconvenient and time-consuming. A better system was soon devised with a helper engine being kept in readiness in order to assist the road engines over the hump.

When the pusher service was inaugurated there was no agent at Cowan. The closest telegraph office at that time was located on the main line at Decherd. If a given train required the assistance of a helper, telegraphic orders were sent to Decherd, and the agent there was required to ride to Cowan on horseback to tell the pusher crew to get up steam and move out to assist the approaching train.

One of the very early rules which covered operations on Cumberland Mountain stated that, "The pusher may ply between Cowan and Tantallon, regardless of all trains,'" This, in effect, caused the trains to hunt the pusher, rather than the other way around. Even so, a pusher was maintained at Cowan on a 24-hour basis. The engine and its crew, the maintenance and section crews, and nearly everything else related to the railroad between Cowan and Tantallon was in charge of Rufe Sartain, better known as the "Mountain Boss,''" Tobe Stewart acted as a special train dispatcher under the "Boss," In this capacity he ordered out the pushers as needed. When light trains, not requiring assistance, traversed the district, Stewart was responsible for protecting the pushers by holding them in the clear. Dispatching operations became much safer and more efficient when telegraph stations were established at Cowan and Tantallon.

Before the days of air brakes the rules required the conductor and brakeman to crawl out onto the car tops and stand to the hand brakes as soon as their train emerged from the tunnel and started down grade. If the crews were slow in their duties, if the track was wet, or if there was any kind of brake equipment failure, the train would soon become a runaway.

The Cowan-to-Sherwood district always represented a traffic bottleneck because of the difficult conditions imposed by the steep grades and sharp curves. In order to ease this situation, a manual two-block system was instituted, with operators located at Cowan, Rockledge, and Sherwood. Although the Division Dispatcher still controlled the routing of trains over this territory, the movements took place on signal indication, with the normal timetable superiority of trains being suspended. The tower operators cooperated with each other in authorizing trains to enter the territory. A written record of each passing train was kept on a "block sheet" to make certain that trains would always be assigned to unoccupied blocks.

The semaphore signals which indicated block status to the train crews were manipulated by the tower operators. Initially, all switches were of the hand-throw type and were operated by the train crews in accordance with the signal indications. After an unfortunate wreck in 1915 the switches at Rockledge were converted for electrical operation from the tower.

The siding at Tantallon was extended to Sherwood in 1916 for the purpose of serving trains of greater length. The new Sherwood switch was operated from the tower at that location by "armstrong" levers, and the north switch (formerly Tantallon) was changed to electrical operation.

When centralized train control was installed on the NC&StL in 1944, the tower at Rockledge was removed. Under the new arrangement the CTC dispatcher assumed direct control of all train movements, even though the system of running trains on signal indication on the mountain did not really change. Coincidentally, the CTC headquarters for the Nashville-Stevenson, Alabama segment of the railroad was located at Cowan at that time.

Despite elaborate safety precautions taken on the hill in the form of signals and special blocks, accidents still occurred. On December 23, 1915, a group of railroad laborers were deadheading home for Christmas on Train No.2, a Chattanooga-to-Nashville local. Opposing Train No. 55, a southbound freight, had arrived at Rockledge at 3:45 P.M. and had taken the siding to await the arrival of No.2. The freight had been assisted to the summit by two helpers. As the two extra engines were being detached and moved away, the Crew of the freight noticed that the signal at the Rockledge south switch had changed to a clear indication. At this particular time the signals were manipulated by the tower operators, but the switches themselves were thrown by the train crews. The crew of No. 55, in accordance with the system of operation in effect, lined the switches to return to the main line and left Rockledge for Sherwood at 3:49 P.M.

Meanwhile, No. 2 had left Sherwood northbound at 3:47 P.M. The trains came together in a head-on collision two miles south of Rockledge. The tender of the passenger train telescoped the car behind it, killing nine of the railroad employees aboard and two of the train crew"

In the investigation following the accident, human error was ruled out. The helper engine crew confirmed that the signal at Rockledge had indeed shown clear. It was suspected that a foreign electrical current had somehow energized the signal, but no hard evidence was ever discovered to support this theory. The next year the track switches at Rockledge were changed over to electrical operation in an attempt to avoid a repeat of this tragic event.

Another notable accident took place on March 15, 1918. The local newspaper described the spectacular event of that day in matter-of-fact terms:

The investigation of this accident was fully as unfruitful as the one following the earlier wreck at Rockledge. Explosions of this sort typically were the result of low water in the locomotive boiler. When this condition occurs, the firebox crown becomes overheated, loses its tensile strength, and ruptures downward, releasing high pressure steam into the firebox. The rear of the boiler is forced upward as a result; tears loose from the engine frame, and is pitched forward end over end, usually landing well in advance of the point of explosion. The running gear of the engine is often not even derailed and this was, in fact, the case in the explosion of the 901.8

Engine crews were not the only employees involved in the dangerous game of railroading on Cumberland Mountain. Rockledge tower was manned on a 24-hour basis during its active years. The tower was located in a remote wilderness area and the operators rode to and from work on a motor car. The car was started by running alongside and pushing it. Then it was a simple matter of hopping on for the ride to Rockledge. A block was, of course, required for the motor car just as for a train. Although no collisions between train and motor car are recorded, one operator was fatally injured when the car struck a rock in the tunnel, and another was killed when the car derailed and tumbled down the side of the mountain.

Trouble returned again with the unusual wreck of Engine No. 571 on April 10, 1950. The engine, one of the well-known J-3 "yellow jackets," had been called out of Nashville to pick up a string of cars loaded with ballast at Cowan and move them south. Upon emerging from the tunnel the engineer could not brake the loading at high speed but was ideal for negotiating the sharp curves encountered in mountain railroading. Special valves providing for steam cutoff at half stroke also found an early application on the "Cumberland.'''·

Down through the years the pushers were traditionally much heavier than the road engines, had significantly greater tractive effort, and were notoriously slow afoot. The heavy stride of the "Cumberland" proved too much when the engine crashed through a trestle in 1859 and was badly wrecked. After a successful rebuilding the "Cumberland" returned to service. It was probably moved south to avoid capture by Federal forces during the unpleasantness of 1861-65 and was finally scrapped in 1866.

The N&C apparently did without a pusher, utilizing 4-4-0's in multiple to assist trains over the mountain until 1870, when a big 10-wheeler with 62-inch drivers and 18" x 24" cylinders was purchased from Rogers Locomotive Works.

Although this locomotive was not the first 4-6-0 on the line, she was a true heavyweight for the day, as evidenced by her nickname, "Big Mary." She weighed 55 tons, compared with about 38 tons for the larger 4-4-0's of her time. "Big Mary" lasted through a long series of numerical designations during her period of service, finally ending her days as No. 170 in service on the Huntsville Branch. In 1933 she went to the cutting torch at the ripe old age of 63 years.

"Big Mary" was joined on Cumberland Mountain by the NC&StL's first consolidation-type locomotive in 1884. This early 2-8-0, officially No. 2, was more commonly known as "Jumbo." Again, the locomotive proved to be the forerunner of many more of its type, this time going to 56 tons in an era of 45-ton locomotives. "Jumbo" operated on 150 pounds of saturated steam and managed a tractive effort of 24,000 pounds with 20" x 24" cylinders and 50-inch drivers. In 1918, when the Rogers-built "Jumbo" had reached the end of the line as a helper on Cumberland Mountain, her running gear and frame were salvaged and utilized under the tender of an unusual experimental duplex engine.

Rogers delivered a second Consolidation to the NC&StL in 1891. This was a larger machine than the "Jumbo," boasting 29,700 pounds of tractive effort and an engine weight of 71 tons. The two Ml's were reserved for the heavy tonnage. The Ml's served through two world wars, but by 1945 they reached the end of the road. In April of that year the required heavy classified repairs were more than the management could put up with and the 2-8-8-2's were dismembered.

At that point helper duties on the hill were taken up by 2-8-2's. Nineteen of these "mikes" had previously been delivered to the NC&StL as a part of the same Baldwin order that produced the three mallets. They were graceful machines with their bulging Vanderbilt tanks and traditional N&C bell stacks. When the mikes took over pusher duty on Cumberland Mountain, it soon became evident that two locomotives would be necessary to accomplish the job which one mallet had handled with ease before. The Ll's were operated in forward or reverse direction and often back-to-back in what became an NC&StL trademark practice. The Ll's were joined by a few slightly heavier 2-8-2's of USRA design and later by L-2B's of 1922 vintage. Engine 664 performed regular duties, lifting passenger trains and light freights over the hill and switching the Cowan yards for many years, and was a well-known pusher district veteran.

The dual service dandies of the NC&StL were the famous J34-8-4's." In their declining days a number of these locomotives served as the last of the steam-powered helpers on Cumberland Mountain. In the autumn of 1952 it was all over for steam on the hill. The J3's were scrapped in September and there were to be no more cinders flying on the mountain.

Helper service presently consists of a lash up of two GP-9's and one GP-7. Today's equipment is striking when compared to the machines of yesterday. The storm on Cumberland Mountain has been somewhat stilled but the grades and curves are still there, and the memory of the thunder returns easily as the diesel engines get rolling behind a heavy coal train southbound out of Cowan. Now the days of steam are over

The helper engines used on Cumberland Mountain became larger and heavier over the years, and concern eventually developed over the safety of the pusher operation. Most of the early rolling stock was constructed with wooden underframes and, although there do not seem to be any recorded instances of crushed equipment, the tractive effort of the big mallets was certainly sufficient to cause this type of accident. As a result, all trains were doubleheaded, with the helper engine on the point, until steel underframes became standard equipment on the cars. At that point freights were nearly always pushed as that was the more convenient alternative. Passenger trains were still doubleheaded, however, just to be on the safe side.

If the helper was pushing a freight, the air was not cut in on the helper, but the engineer was under instructions to keep his hand on the throttle at all times in order to shut off in case the train brakes were applied. When the helper was on the point, the air was cut in and the lead engine took the signal indications and controlled the train.

When pushing, the helper always bunched up the slack and started the train moving at the foot of the hill. On arrival at the top the pusher would cut off on the fly prior to entering the tunnel. This practice was necessary, for once the head end of the train passed the summit and started to roll down the other side, the stretching of the slack against the pusher would have caused knuckle or drawbar failures. When things got busy on the hill, the helpers would assist one train over in one direction and get right on another one coming back. In these cases the helper was placed on the point so that the engine could run all the way through without the inconvenience of cutting off and following a train down grade.

A pusher crew normally consisted of an engineer, a fireman, and a brakeman. During World War II there were ten or more such crews working in the district, with as many as three or four on duty at one time. The crews have always worked on a first in-first out basis rather than on a regular shift. The seniority of these engine crews was confined to the pusher district itself, although many of the men did work on other branches from time to time. The pusher crew has recently been reduced to two men. A yard conductor joins them on the first shift, however, to supervise switching operations at Cowan. Some hostlers are also employed to service the diesels and call the crews.

Riding the pusher engines over Cumberland Mountain can be a memorable experience:

February 19, 1972, was a sharp, cold day. There was some snow in the air that morning. Engineman R. H. (Roy) Smith and brakeman H. L. (Pete) Coutta were waiting for their first assignment at the engine terminal just north of Cowan. Their pusher lash-up consisted of GP-7 487 sandwiched between GP-9's 526 and 529five thousand horsepower ready and waiting.

Shortly the "Widow's Creek Turn," a 7400-ton trainload of coal bound for the TV A steam plant near Stevenson, Alabama, came roaring into Cowan with the wind from the north. The dispatcher ordered the pusher out to assist the coal drag which had been led into town by a pair of SD-40's and a single SDP-35.

On the first try at hooking up to the rear of the train the coupler pin failed to fall. Road engineer H. A. Tidwell came on the radio, "Hit it again, Roy. You won't hurt it!" Once the joint was made the pusher nudged into the train. "We're moving on the head end," reported Tidwell. Since the pusher had already moved a considerable distance, engineer Smith felt compelled to reply, "You'd better be!"

The pushers worked easily down to the foot of the hill in town and then the speed dropped off. Below the first curve to the left Smith turned loose the sand. The pusher engine cab was a busy place for the next few minutes. Just as it began to look like the train might stall on the hill, the speed picked up a bit and brakeman Coutta climbed down on the floorboards. As the train rolled over the summit inside the tunnel he pulled the cut lever and disconnected the pusher on the fly.

After the train cleared the tunnel the pusher followed on down the hill running light, on past Marlowe Field where many of the laborers who had died of cholera during the construction of the N&C lay buried; on past Hominy Hill, the site of the tragic accident of the 1915 Christmas season; on through the deep cut where ice hung in a great drapery on the vertical rock walls; on to the road crossing at Tantallon, which was saluted with a resounding blast of the air horn; and on to an easy halt at Sherwood with the bell announcing the arrival of the pusher on the south side.

As the crew changed ends on the pusher the conversation turned to things of another time-fast trains, mistakes made, discipline meted out, and home guard railroaders long since gone. The interlude was interrupted by the arrival of northbound train 688 (80 empties and 31 loads) led by three U-30C's. Brakeman Coutta took up a position on the far side of the arriving train and made a complete inspection of the rolling stock running gear. "All black,"" he reported as he climbed back up into the pusher cab.

With the joint made the pusher went to work again, shoving Engineer C. A. Woods' northbound string up along Crow Creek, sparkling in the midwinter sun. Smith worked the throttle open and applied the sand. This time the locomotive exhaust echoed sharply off the walls of the cut. The storm returned to Cumberland Mountain.

At the south portal the pusher cut off and stood idling once again while the freight drifted on down to Cowan. With the work done for the moment and the train ahead in the clear, the CTC dispatcher called the pusher and issued the welcome order, "C'mon, c'mon to Cowan!" So it's goodbye, Cincinnati

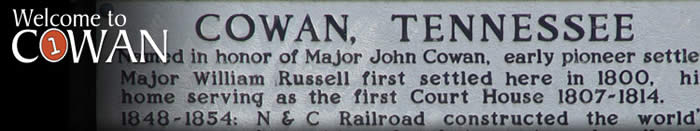

The people of Cowan think of their little town as a very special place. They have come to recognize those unique elements which lend character to their city. Cowan is first and foremost a railroad town. As a first step in their efforts to revive their community, the citizens have developed a park in the center of town along the L&N mainline. Thus, beauty was created in an area where only a pile of cinders existed before.

The grassed areas, plant materials, fountain, and flagpole are bordered by a brick wall decorated with wrought iron. The historic marker which stood inaccessible at the north portal of the tunnel for many years has been moved and re-erected on the depot site. All of these recent improvements have been designed with taste and constructed in professional fashion. Visitors and citizens alike can now enjoy train watching from this most pleasant vantage point.

As a next step the people of Cowan, who have organized themselves as the Cowan Beautification Commission, plan to restore and renovate the 1904 depot building. The structure will be given to the cause by the L&N (provided that the local group can secure its removal to a safe location across the tracks from its present site).

The exterior of the depot will be restored to its 1915 appearance, while the interior will be renovated for the purpose of housing a railroad museum and local history collection. Interpretive displays and models will supplement exhibits of memorabilia. The depot tower will be remodeled and arranged to accommodate train watchers.

The Commission is currently seeking railroad rolling stock to be set up as a static outdoor display in the park. A baggage car and caboose will likely be selected and acquired soon. This equipment will receive interior modifications for use as a public library. As a final step a picnic grove will be built as a convenience for visitors.

The Cowan Pusher District continues in operation today as it has for over 120 years. The mainline railroad activities which currently take place at Cowan are an important part of a viable modem transportation industry. The development work being carried out, although it honors the past, is very much a thing of the present. The character of the city is being preserved and in the process Cowan is finding new life. To experience the feeling in this unique community one need only heed the dispatcher's order, "C'mon, c'mon to Cowan'"

1 Paper delivered by President W. S. Hackworth of the Nashville. Chattanooga, and St. Louis Railroad before the Round Table Club of Nashville, Tennessee, on March 26, 1953, p.9. 2 The 1850 Census of Franklin County shows that there were three labor camps at Cowan, with over 200 laborers, all "working on the railroad" tunnel. Of these 55% were natives of Great Britain (largely of Ireland). Their median age was 23. Of course, there were other laborers on the project: slaves, married men, and residents of Franklin County, who do not show in the camp listings.

3 William H. MacKellar, Chuwalee, Chronicles of Franklin County, Tennessee (Winchester, 1973), 88. 4 W. H. Smith, "Reminiscence of an Old Timer," in NC&StL Railroad News Item, October 1926, p.14.

5 Rufe Sartain, at one point in his career, was seriously injured when he fell off the pusher. He lost one leg as a result and was attended by Major John W. Thomas (President of the NC&StL Railroad, 1884-1906) during the emergency operation which followed the accident.

6 The only railroad accident in the United States with a death toll in excess of 100 occurred on the NC&StL Railroad near Nashville on July 9, 1918. See Down Brakes, by Robert B. Shaw, for details of this and other major railroad disasters.

7 Winchester Truth and Herald, March 21, 1918, p.l. 8 Boiler explosion causes are discussed in detail in The Steam Locomotive in America, by Alfred W. Bruce, pp. 136-137. An accident with results similar to the catastrophe occurred on the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad near Spence, Wyoming, on December 24, 1916. A detailed account of this event is contained in the Bulletin of the National Railway Historical Society, Vol. 39, No.5, 1974, pp. 20-27.

9 Steam locomotive types are often described by indicating the wheel arrangement according to the Whyte classification system. Thus, a 4-4-0 “American” type had four leading (pilot) wheels, four large diameter driving wheels and no trailing wheels. Some larger articulated locomotives had two sets of driving wheels and this arrangement required a four digit description (e.g., 2-8-8-2). 10 The construction of this locomotive and others of 0-6-0 wheel arrangement followed the successful patented Baldwin design of 1842.

11 David P. Morgan, "Gliders, Yellow Jackets, and Stripes," in Trains Magazine, December 1963, pp. 22-35.

12 "All black" is the railroad term for a train operating with cool wheel bearings and no smoking or hot journal boxes.

|