|

The Way We WorkedTom R. Knowles, Jr. Curator, Cowan Railroad Museum V.P., NC&StL Preservation Society Article was written in preparation for Cowan Railroad Museum's hosting a traveling Smithsonian Exhibition entitled "The Way We Worked" in the spring of 2012

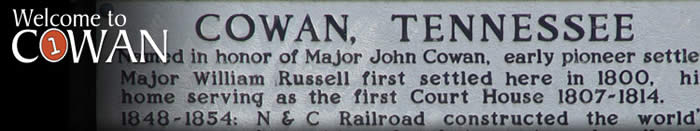

The beginning The small city of Cowan, Franklin County, Tennessee has a long history as a “working” town. Much industry has occurred here as a result of a good location and having people with strong work ethic. The co-incidences for success abound, with local access to resources and even now, excellent transportation.

Early Indians The people who have lived here for centuries (formerly Cherokee) have found all the things they needed to live a good life, including decent weather, good water and abundant food. Cowan is situated in such a location that first provided some protection from predators both animal and human. It is likely that very early traders walked and rode through this area since the low point in the mountain range for crossing into the Crow Creek valley towards the S.E. was easily visible upon approach from the valley floor. It is widely known that many of today’s routes lay where Native Americans and game trod.

Early settlers By the middle of the 19th Century, European Settlers had displaced most Cherokee in this region, and the new entrepreneurs had caught “Rail Road Fever”. That is, investors, politicians and businessmen eagerly foresaw the economic advantages to having a smooth and efficient transportation system. As a huge improvement to wagons, skids and horseback, over roads that frequently were flooded or otherwise impassable, this transportation system would allow an enlarged marketplace (World-wide) providing reliable prosperity for all.

Access South through Cowan Prevalent at Cowan (previously known as “Hawkins”) a “low spot in the toe of the mountain” was not lost on engineering genius J. Edgar Thompson as he rode on horseback through our valley, surveying an advantageous route for the future rail road. (Note the two separate words, as they were used in the beginning) The intended route was to connect the Capitol at Nashville to the seaports at Savannah, Georgia. The Tennessee legislature granted charters to such ventures and financing was arranged. Land was obtained along the general vicinity of Mr. Thompson’s survey, and work was begun near Hawkins, digging by hand a tunnel through the mountain at the low spot seen from afar. Rails had not even been laid past Antioch by the time the tunnel was finished. It would end up in 1852 being the wonder of the age and is still in use today, listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It was 2221ft long, dug 17 Ft high and 14 Ft wide, and was elevated in the center at 1147 Ft. It was so large and well constructed that it did not require enlargement until 1960. Name change and minerals During this time, Hawkins became “Cowan”, in honor of Dr._____ Cowan who resided in the area. Shortly after the rails finally reached Cowan, mined coal as a fuel was becoming the heat-source of choice. Coal deposits were discovered on the Cumberland Mountain near present day Palmer, TN. and in 1855 the Sewanee Mining Company was formed to construct mines and a railroad to transport the “black gold” down the mountain for main line access at Cowan. Large limestone and sand deposits were also discovered. The connection was via a switchback and bridge (s) over the existing mainline at the tunnel north face. In those days there was only one set of tracks down to Cowan from the tunnel. About 1900 the tracks were re-arranged and until 1985 (?) there were two that proceeded from the tunnel to Cowan. By that time the mining branch was known as the Tracy City Branch of the NC&StL (Nashville, Chattanooga and St Louis Ry) with a nickname of “Mountain Goat”.

New University In 1857 The Episcopal Church was searching for a site to institute a new seat of higher learning. A Bishop Otey and others selected a 10,000 acre plot astride the mining company track at the edge of the mountain, as a gift from the mining company. The University of the South was born, and benefited from rail transport in its development. It also suffered because of it during the War Between the States as the Union Army found its location useful. As that Army advanced south, the first Cornerstone that had been laid there was blown to bits, and other vandalism to buildings caused a temporary setback. After the War, there resumed with new resolve to build a showcase campus with excellent curricula. It is called the University of the South at Sewanee and today through hard work has attained that coveted status.

Cowan Crossroads. Times were tough in post-war South for many reasons, not the least of which were to burden of repaying the Union for infrastructure improvements claimed to have been made during the war. Cowan benefited from all this coming and going, and soon became a crossroads of sorts. A building boom erupted here about that time with new buildings, streets, railroad infrastructure with a new spacious and bi-racial depot built. Two railroad lines and a new US highway intersected here at the foothills of the Cumberland.

The Sewanee Mining Company eventually became the Tennessee Coal and Iron Company (through several variations in the name) and struggled financially, thus went into receivership. The NC&StL Ry bought receivership rights and renamed it the Tracy City Branch, investing in its improvement. Thus, much freight and passenger traffic was generated off the Cumberland Plateau to and through Cowan. Cowan was also the location where railroad travelers would get off the train for their meals, as railroad dining cars had not yet been invented. They ate at places like the “Commercial Hotel” (Hodges?) and were given thirty minutes to complete their repast. At one time sixteen passenger trains a day were scheduled through Cowan. On the Tracy City Branch, there were eight. Countless freight and work trains also plied the rails here.

A new road was being built little by little that generally traversed from Chicago to the newly popular destination of Florida. That was called (and posted as) the “DH”, short for Dixie Highway. This is the route where US highway route 41A more or less lays today. That route took travelers through Cowan also, where one could rest, eat and re-supply before climbing the mountain. One could also board a train and ship goods from here.

Pushers, Open Hearths, Lumber, Cement, shirts and shoes Already having sawmills and gristmills and a railroad to maintain, Cowan was a big participant in the industrial revolution. From the very beginning, Cowan was selected as a flatland staging point for trains hoping to ascend the mountain and through the Cumberland tunnel. Being a heavy grade in both directions to the Tunnel, extra locomotive engines were usually added to trains as an assist. Since trains had to stop to add this feature, and passenger trains were already stopping for meals, more tracks were added to facilitate the standing and passing of trains. As well, steam locomotives by nature required much attention to operate safely and properly. A small repair and service facility grew up in Cowan, and pusher or “Helper” engines have always been stationed here. Steam locomotives were converted from wood fuel to coal during the 1870’s. So the coal at Palmer found its way into many of the NC&StL engines, requiring increased traffic in Coal from Palmer, TN and work for the miners.

It took a large crew to keep the engines running and trains moving here, so it is not hard to imagine that up to 200 people were engaged in rail transport in Cowan at any given time in the not-so-distant past. A 1920 census shows 73 white people (one was a woman) and 40 blacks living in Cowan employed by the railroad. Some were as young as 14 and some were over 70 years old. Many people were employed here that lived elsewhere. The 1910 Census shows 837 as Cowan’s population, this is a large percentage of residents gainfully employed by the Railroad. As the Railroad was progressive in many ways, including employee relationships, it was one of the first large Railroads to completely convert to Diesel Locomotives (Jan 1952) thus ending the need for so many maintainers. Today pusher engines still help large heavy trains “over the hill and into the hole”. Large two unit Diesel locomotives of 5,000 HP or more each are dispatched on about three-quarters of the trains proceeding southeast. Now there are perhaps 20 people who help keep the trains running here and only one or two RR employees live here.

Cowan became an important site for the making of iron during the close of the 19th century. Raw materials and fuel for the open-hearth process were abundant and close at hand. Coal was coked at Tracy City and brought down as fuel and a carbon source for the process. Limestone is the flux in reducing iron ore to iron, and that also is plentiful. There is so much leftover product from iron smelting called “slag” that was thrown away during this process, that there is an area of town called “Slagtown”. Slag fills a natural ravine that is 30 Ft deep in places now full and level with surrounding land. It stretches for about a half mile in length, proof to the volume of Pig-Iron that was produced right here in Cowan.

Wood was a vibrant business during the period, having a large sawmill that transformed raw timber into finished lumber. Located right next to the NC&StL mainline, it received carloads of timber from the Davidson, Hicks and Greene, Cumberland mountain operation. This was a huge operation, having over 200 miles of track meandering through the forests of the plateau, even extending into Alabama some 40 miles for virgin hardwood timber. As the timber was logged off, business dwindled, so the site was selected for a new venture. Also important was the production and shipment of some 60,000,000 spokes for the wheels of Henry Ford’s new “Model T” car, produced on the plateau and shipped through Cowan.

Cowan is also famous for in its hey-day making some of the best Portland cement in the world. Portland cement is made using coal, limestone and sand, all readily available on the Cumberland Plateau. This product was made in a plant that replaced the lumber mill operation, also adjoining the mainline tracks and connected via the branch line track to Cowan yard. This operation began about 1928 and finally closed it doors in 1980 due to a number of factors. Over 2 million man-hours of work were done here without a lost-time accident. At the same time, a large factory was built right downtown that produced shirts, shoes, flocked goods and a variety of soft goods over the years. This 20,000sq.ft. building survives today in use as a small business incubator and large meeting or convention center.

Closing The support industries of such a productive local society then also flourished: barbers, grocers, druggists, jewelers, cleaners, wagon then auto repair, tire recapping, hotels, eateries, fuel distributors, an automobile dealership, gun shop, movie theatre all existed here. All worked for the good of the other and for themselves. There still are ten Churches. Their industry was felt world wide, many prospered. Many still do prosper in this community, as teachers, fire and police people, hotels, eateries and other services are making a comeback. The legacy is carried through now as a quiet community with hopes for the future and with a great sense for the artistic: there are performing arts, and other wonderful artisans who work here. Different from the past but still industrious. People here still have a tenacious sense of community and history. The way we work today will become the way we worked.

|